LockBit 3.0 - An In-Depth Analysis Of LockBit Black's Config

Inside the world of ransomware dissecting the attack

After some time of respite in the world of ransomware, different players in the field started rebranding their operations. Recently, one of the most active groups returned. The notorious LockBit group introduced a new strain of their ransomware, LockBit 3.0. More specifically, the threat actor dubbed its latest release LockBit Black, enriching it with new extortion tactics and introducing an option to pay in Zcash, in addition to the already offered Bitcoin and Monero crypto payment alternatives.

Additionally, as a first in the ransomware world, LockBit launched a bug bounty program with rewards ranging from a thousand to a million dollars. Confident of its privacy, the affiliate manager, known as LockBitSupp, offers one million dollars for anyone who can reveal his real identity.

Within the infosec community, several analyses showed that LockBit 3.0 seems heavily based on the BlackMatter codebase, hence the name LockBit Black [1, 2]. Following our previous whitepaper on LockBit, Northwave obtained a sample of the latest strain and performed an in-depth analysis. Additionally, Northwave tried to recover the config and extracted information that could help during incident response engagements and support the root cause analysis. This blog presents the method for extracting the config from a LockBit Black sample and describes the included fields and functions.

Furthermore, Northwave published an open-source IDAPython script for analysing the config and scripts to perform the necessary string decryption and API call deobfuscation. Finally, Northwave will add a command-line tool for dumping the content of the config. All of this is available on Northwave's GitHub.

Config decryption

Unlike BlackCat, which included its config in plaintext up until recently, the LockBit 3.0 authors exert extreme effort to hide their configuration details.

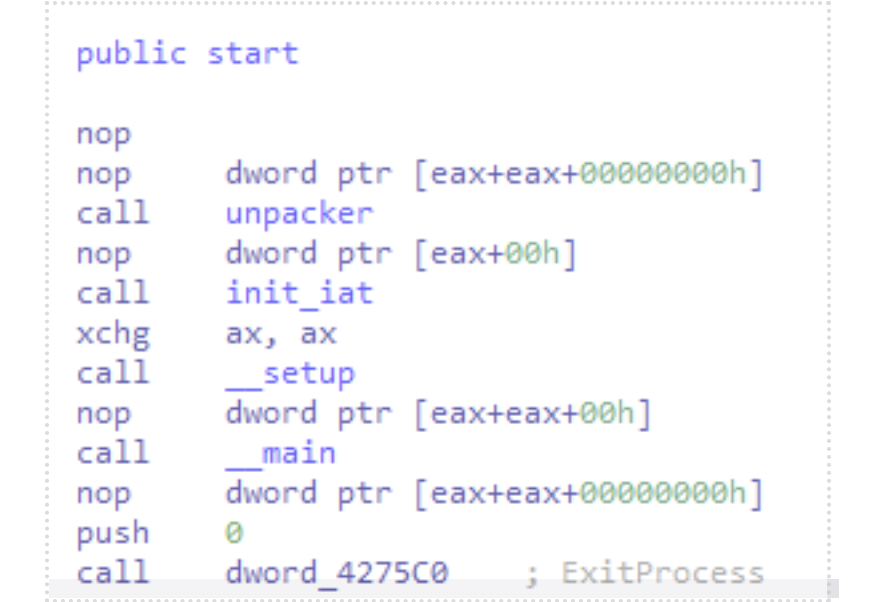

The malware starts by unpacking itself in place (a good hint is given that the

.text

segment is Read-Write-eXecute) and then initialises its custom Import Address Table for calling API functions.

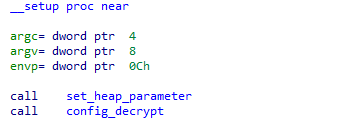

After these two initial steps, the malware begins executing, starting with a call to a big <code>__setup</code> function. This entire function mainly concerns running functionality to configure and prepare the environment for successful ransomware execution. Many of these steps depend on values from the config; hence, we see the config decryption function being called very early in the setup stage.

Again, LockBit takes extra measures here to protect its most important data. Rather than just decrypting once, it takes numerous decryption, decompression and decoding steps to extract the entire config. From our analysis, we observed that LockBit splits its config decryption into three main parts:

- Config blob decryption

- Variable block processing

- String block processing

Blob decryption

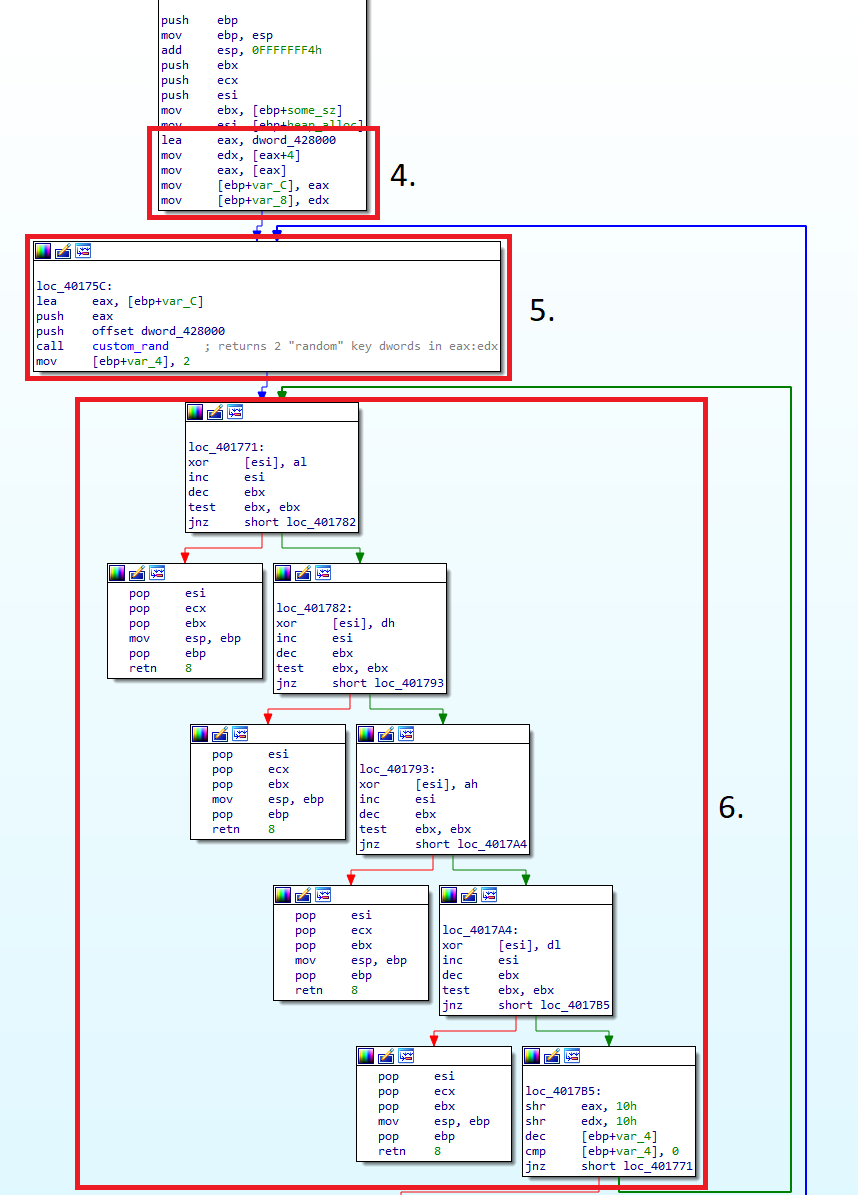

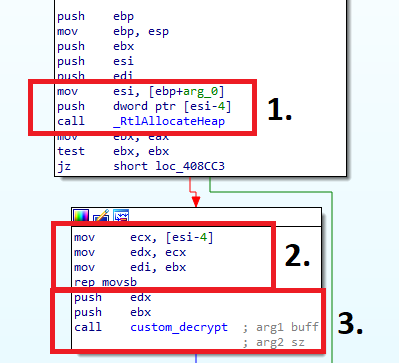

Before one can access any of the config's individual sections, full decryption must occur. In the sample, we can see that it takes a pointer to the start of the config and takes two steps (custom decrypt, aplib decompress) to decrypt it fully.

The `load_and_decrypt_config_value` function contains logic for the config's decryption, its values and the decryption of values in the data segment. This function works as follows:

- Take the pointer to the start of the encrypted block, read out the 4 bytes preceding it to get the size, and allocate it.

- Copy the encrypted blob into the newly made allocation using the given <code>size</code>.

- Pass the allocation and its size to the decryption function.

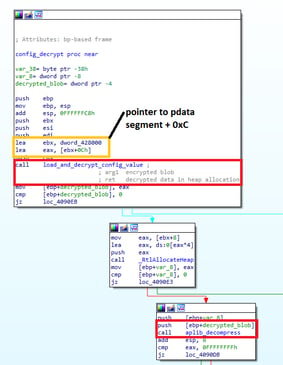

- Once again, take the pointer to the start of the config section, and read out the first two dwords. The <code>custom_rand</code> function uses these two dwords as a "seed".

- Call the <code>custom_rand</code> function with the two dwords and a pointer to the config section as arguments. This function returns 2 "random" dwords used as a key in step

- Use bytes from the two random dwords and use them to decrypt the encrypted blob (8 bytes at a time).

NOTE: The <code>custom_rand</code> function is generated dynamically and needs to be either decrypted separately or viewed inside a debugger.

As the decryption uses dwords generated from a given seed that is constant for a given sample, it is unnecessary to decrypt each blob 8 bytes at a time. Instead, with careful analysis, it is possible to convert the decryption scheme into a "keystream" generator that can generate a potentially infinitely long stream of key bytes based on the seed for a given sample.

We have taken some time to write this out in c for clarity. Below you will find the decryption scheme transformed into a key stream generator that one can use to decrypt any encrypted blob in the sample.

/*

These variables might need updating

for newer samples. You can find these

inside of the function that implements

the logic inside of "custom_rand()"

*/

uint32_t VAR1 = 0x5851f42d;

uint32_t VAR2 = 0x4C957f2d;

uint64_t VAR3 = 0x14057b7EF767814F;

uint64_t

some_algo(uint32_t v1, uint32_t v2 ,uint32_t k1 ,uint32_t k2)

{

uint32_t tmp;

uint64_t tmp2;

if( !(v1 | k2) )

return k1 * v2;

tmp =(k2*v2)+(k1*v1);

tmp2 = ((uint64_t)k1 * v2);

return ((tmp2 & 0xFFFFFFFF ) | (((tmp2 >> 32) + tmp) << 32));

}

uint64_t

custom_rand(uint32_t *state, uint32_t *consts)

{

uint64_t v;

v = some_algo(VAR1, VAR2, state[0], state[1]);

v += VAR3;

state[0] = (v & 0xFFFFFFFF);

state[1] = (v >> 32);

return some_algo(state[1], state[0], consts[0], consts[1]);

C

}

/*

Rather than decrypting the config the way the

binary does, we can create a long stream of key

bytes ahead of time.

*/

uint8_t *gen_keystream(uint8_t *start, size_t *bytes_generated)

{

int i;

uint64_t x;

uint8_t *ret;

uint32_t *tmp_ptr;

size_t len;

tmp_ptr = (uint32_t *)start;

// Get first 2 dwords from config

uint32_t consts[2] = {tmp_ptr[0], tmp_ptr[1]};

uint32_t state[2] = {tmp_ptr[0], tmp_ptr[1]};

len = tmp_ptr[2] + 8;

ret = malloc(len);

// Perform the byte mangling according to spec

for (i = 0; i < len; i += 8)

{

x = custom_rand(state, consts);

ret[i + 0] = ((x & 0x00000000000000FF) >> 0 );

ret[i + 1] = ((x & 0x0000FF0000000000) >> 40);

ret[i + 2] = ((x & 0x000000000000FF00) >> 8 );

ret[i + 3] = ((x & 0x000000FF00000000) >> 32);

ret[i + 4] = ((x & 0x0000000000FF0000) >> 16);

ret[i + 5] = ((x & 0xFF00000000000000) >> 56);

ret[i + 6] = ((x & 0x00000000FF000000) >> 24);

ret[i + 7] = ((x & 0x00FF000000000000) >> 48);

}

*bytes_generated = len;

return ret; }

Variable block

After decrypting and aplib decompressing the entire config blob, the parameters inside of the variable block become visible. In our sample, this block was

0xB8

bytes long and contained three values. More on the meaning of the values later.

String block

The string block is slightly more obtuse as opposed to the variable block. The string block is formatted using a header with an array of offsets from the base of the string block to base64 encoded strings. There is no clear way of finding the size of this array except for analysing the config decryption function. In the case of our sample, it supports up to ten entries. However, there are not guaranteed to be ten because individual offset entries can be 0, in which case the string is ignored.

The first eight entries just require a base64 decode. The last two entries need additional decryption.

For a complete overview of the decryption steps described above, please take a look at our example IDApython script for dealing with LockBit's config.

Config values

After decrypting the config, the following values will remain.

Variable block

| offset | value |

|---|---|

| +00h | RSA-1024 key; First 8 bytes also used as an ID in some cases |

| +80h | Company ID |

| +90h | Unused |

| +A0h | 24 byte array of boolean values. This is used to enable or disable functionality (see Boolean Config below for more details) |

| +B0h | Start of base64 block offset array |

| +D8 | Start of base64 block |

Base64 block

| entry # | value |

|---|---|

| 01 | Folder exclusion hash list; Each entry is a dword hash of a folder name such as {"Windows", "Program Files", "$recycle.bin"} that will be excluded by the encryption loop (For more info on the hash algorithm, see the github |

| 02 | File exclusion hash list; Each entry is a dword hash of a filename such as {"desktop.ini", "autorun.inf", "ntldr"} that will be excluded by the encryption loop |

| 03 | File extension exclusion hash list; Each entry is a dword hash of a file extension such as {"ANI", "CAB", "COM", "SYS", "MSI"} that will be excluded by the encryption loop |

| 04 | Computername hash list; A list of hashed computer names that will be excluded from specific actions (such as setting the desktop wallpaper, enabling safeboot, disabling privacy settings experience, etc) |

| 05 | unused |

| 06 | Plaintext list of software names such as {"sql", "oracle", "synctime"}; The malware will attempt to terminate the software in this list |

| 07 | Plaintext list of service names such as {"msexchangem", "veeam", "sql"}; The malware will attempt to disable and remove the services in this list |

| 08 | unused |

| 09 | Plaintext list of credentials in the format of username:pass used to set the default logon for the system |

| 10 | The ransomnote |

Boolean config

Functionality activated if the value is set unless states otherwise.

| index | Value | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 00 | LB3_ENCRYPT_ANY_BIG_FILE | If this value is not set it will only perform proper encryption of the following big file formats {.MDF, .NDF, .EDB, .MDB, .ACCDB}, any other file formats will only get a quick encryption done |

| 01 | LB3_RANDOMISE_FILENAME | |

| 02 | LB3_AUTHENTICATE_USING_CREDS | This flag is used in combination with the credentials stored in the 9th entry of the base64 block |

| 03 | LB3_SKIP_HIDDEN_FILES | |

| 04 | LB3_LANGUAGE_CHECK | Perform the common slavic and related languages check and don't encrypt the system if one is set on the system |

| 05 | LB3_ENCRYPT_MICROSOFT_EXCHANGE | The functionality belonging to this flag attempts to mount some extra volumes in addition to specifically looking for a microsoft exchange folder to encrypt |

| 06 | LB3_ENCRYPT_NETWORK_SHARES | |

| 07 | LB3_KILL_PROCESSES | Used in combination with entry 6 of the base64 block |

| 08 | LB3_KILL_SERVICES | Used in combination with entry 7 of the base64 block |

| 09 | LB3_CREATE_MUTEX | |

| 10 | LB3_PRINT_SIMPLIFIED_RANSOMNOTE | Enumerate local and network connected printers and print a simplified ransomnote |

| 11 | LB3_SET_BACKGROUND | |

| 12 | LB3_REGISTER_ICON | |

| 13 | LB3_ENABLE_C2_LOGGING | LockBit has the ability to communicate some basic information back to a C2 server |

| 14 | LB3_SELF_DESTRUCT | LockBit carries an additional executable with it that is activated if this flag is set and some error conditions are encountered (such as mutex already being set). It appears that the entire purposLockBite of this executable is to self-destruct the malware. It terminates the ransomware process, overwrites and renames the executable on disk (it actually renames it 26 times for each letter of the alphabet..), removes the executable and then uses a shell command to remove itself as well. LB3_SELF_DESTRUCT_2 and LB3_SELF_DESTRUCT_3 appear to be used to perform some additional cleaning in some cases. |

| 15 | LB3_ATTEMPT_UAC_BYPASS | |

| 16 | LB3_SELF_DESTRUCT_2 | See LB3_SELF_DESTRUCT's note |

| 17 | LB3_RESTART_PROCESS_WITH_PSEX_FLAG | |

| 18 | LB3_RESTART_PROCESS_WITH_GSPD_FLAG | |

| 19 | LB3_UNKNOWN | |

| 20 | LB3_SELF_DESTRUCT_3 | See LB3_SELF_DESTRUCT's note |

| 21 | LB3_CLEAR_EVENT_LOGS | |

| 22 | LB3_PROPAGATE_THROUGH_NETWORK | |

| 23 | LB3_RESERVED | The last byte in the array is not actually used, but is allocated |

Conclusion

While LockBit Black looks to be taking much of its code from the BlackMatter ransomware, the codebase has seen quite a refresh. With the config and other parts changing substantially, we deemed it time for an update to the existing knowledge. We hope this analysis and the tools provided will benefit the infosec community and support CERTs worldwide dealing with LockBit cases.